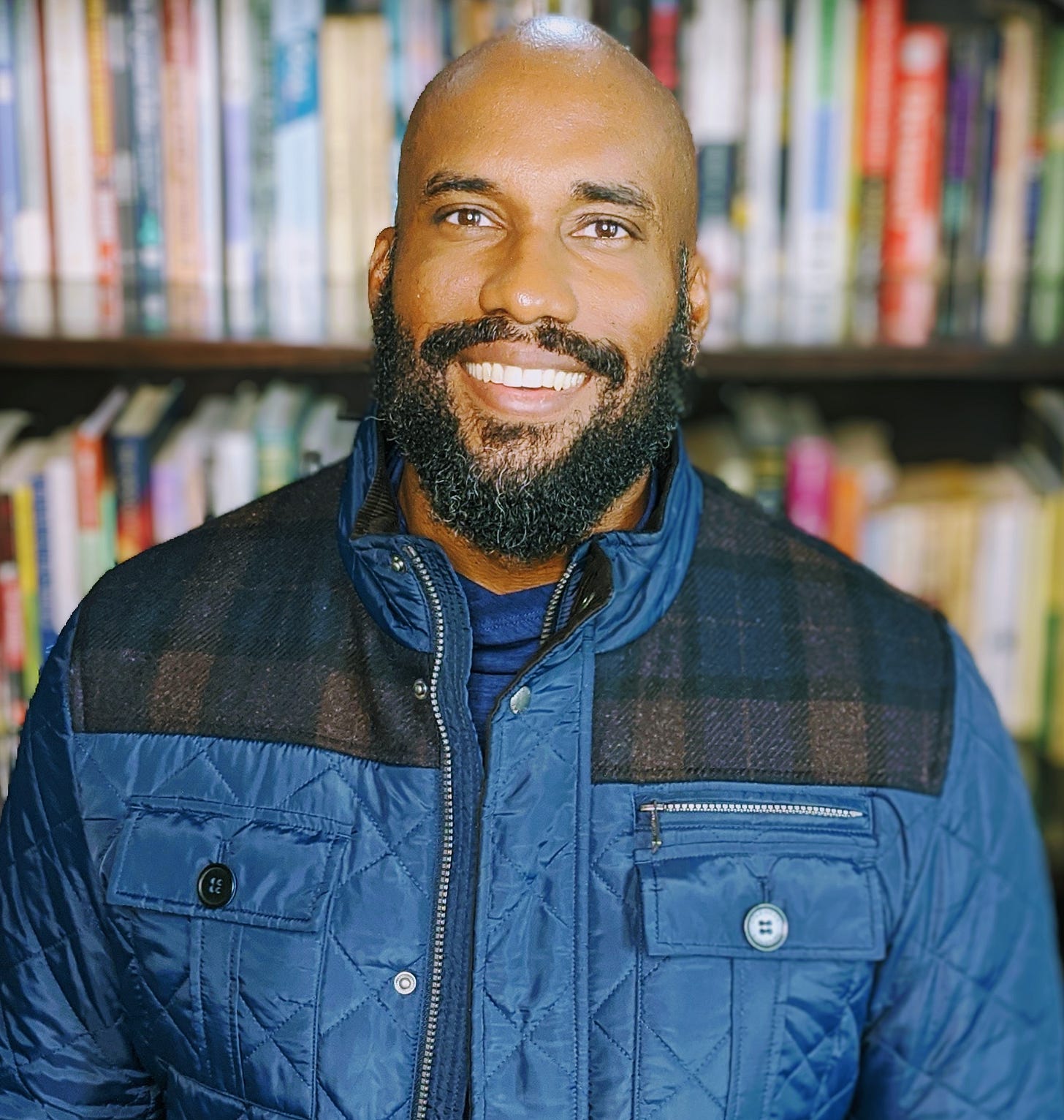

Burnout is a common problem for leaders, but it’s something we don’t talk about often. I’m happy Anjuan Simmons, Staff Engineering Manager at GitHub was willing to talk about his experience and what he’s learned. We spoke about how Star Trek got him into engineering, what makes leaders susceptible to burnout, how to become more burnout resilient, and how to support those you think are at risk for it. There are so many great gems in this episode for every leader.

We met in New York about a year ago, I think, at LeadDev.

That's right. I was at one of your amazing workshops where I learned a lot from you. It was awesome.

You're so sweet. And I saw you give a great talk at LeadDev a few years ago.

That's right. I've been very lucky to do a number of talks with the LeadDev conference series. The one that I think you're talking about was a talk on burnout. How appropriate! But I've done talks like “Lending Privilege” which is about inclusion and is probably the talk that I'm known the most for. LeadDev is a great organization for tech leadership, and you and I have been very lucky to be a part of its mission and community.

There are a lot of LeadDev guests on this show because it's a great community. So obviously, we know each other, but can you share a bit of background about yourself for those who don’t know you?

Absolutely. I’m Anjuan Simmons, and I’m a technologist. I've been in the technology industry for my entire career. I earned my electrical engineering undergraduate degree at the Univesity of Texas at Austin. After I graduated, I worked at Accenture, and that's where I learned how to do very large enterprise software implementations. I left Accenture to get my MBA, and I then worked at Deloitte which was another large consulting company. So I started my career in technology at large multi-billion dollar global companies, and that's where I learned about all the rigor and the structure of working on software.

But, I then worked at startups, and so I had a long career with much smaller

companies, many of which no one's ever heard of, but were great experiences. I learned a lot working at startups. I like to say that my style as an engineering leader is a lot of the rigor and structure that you get from big companies like Accenture and Deloitte but with the personal touch, and the wearing of multiple hats that you have to do at startups.

Today, I am a Staff Engineering Manager at a lovely company called GitHub, and that's what I'm doing now. I am the Engineering Manager responsible for GitHub Sponsors.

Before we talk about burnout, can you tell us a little bit about your path into leadership? Was it something you sought? Something you expected?

I never saw myself as the leader or the manager. I got into tech because, in many ways, Star Trek (a show TV that I was into in junior high), focused on the bridge, but what I loved was engineering and seeing Scotty in “The Original Series” and Geordi La Forge in “The Next Generation”. Both characters really put me in the mind of, "That's what I want to do. I want to be the engineer, not the captain doing the boring stuff like figuring out navigation and making big decisions and dealing with personnel. Give me the warp engines, give me the warp drive."

As I got into work and became a software engineer, I joined a company called Accenture. I eventually realized that Accenture is an up-or-out company, which meant that you join as a software developer, but you need to make the next promotion and then the next one. If you did not hit the promotion milestones, well, they asked you to leave. To stay at the company and to keep going up was required, so that's what I did.

The good news is that I loved it! I enjoyed having the ability to have an impact, to have influence, and to help projects run smoother. More importantly than that, the opportunity to develop other engineers, because if I became a really good engineer, that's one thing. But if I could help five people become really good engineers, well, that's more really good engineers out there. So that's a big part of why I love management and why I love leadership. It's the opportunity to have a demonstrable impact on people's lives.

I felt that my legacy in software would be better served by becoming a manager than by continuing as an engineer. One other point is that the software industry has caught up to the idea that you should not force people to become managers in order to keep them going up the promotion chains. While some companies haven't gotten that memo yet, most companies, including GitHub, very much have two tracks that are respected, and that are well compensated. You can go the individual contributor route and go from an intern up to senior, to staff, to principal, to distinguished, and have influence and not have to deal with the people management stuff. Or, you can also take the standard engineering manager route where you are doing more of the people development, more project planning, and things like that. Both of those tracks are respected and supported.

I love your point about those two tracks. My father was a mechanical engineer at General Motors. There was no path for him as an individual contributor with lots of expertise. Unfortunately, the leadership didn't understand folks like him. I love that we're beginning to see that happen in companies more and more.

Absolutely. Often when you force engineers to become managers you often lose really good engineers because people management is hard and people leave the industry because they were forced to do it. Or, you create really bad managers because that's just not their jam, that's not their core skillset. I think that having both tracks is many in ways, the best of both worlds. You give people choices, and they can develop their careers in alignment with what they're really good at.

I think it's related to burnout. Sometimes we might be in a role that we're burning out because we're not in the right role. You had an experience, a burnout. What was going on? How did you recognize you were there?

I've experienced burnout at various points in my career. I think that there are a lot of things built into the software development industry that make it much more susceptible to burnout than people realize. I think people often think that "Well, you work in software, you work in these plush offices that have all these great amenities and you even have beer on tap in the break room and you have all this access to cool software tools. You work in a cool pod with an amazing multi-monitor setup and a $10,000 chair that you sit in. How can you be burned out? You're not building bridges, you're not building buildings, you're not digging ditches."

I think people fail to realize that there are all kinds of stresses that we put on people in our industry. One that comes to mind is the fact that our industry always changes. You have to constantly keep up with the newest technologies. The things that I used when I joined this industry back in the '90s, well, most of that stuff doesn't exist anymore. And a lot of the things that we do today, that are routine, did not exist back then. I've had to learn about all the different tools and techniques. We didn't have Kubernetes or Docker when I started my career. Those are all very common development tools now. So the almost unending need to keep up can be extremely stressful, and that by itself can be a contributor to burnout.

Then there's also the almost constant need to keep shipping. I think a common phrase that people use is, "Always be shipping, always keep shipping." But the reality is that anything that is always on will fail. It's really important that we understand that people have natural limits that we should respect.

The first time that I became really aware that I was burned out, and it's been many years ago, was when I was working on a project in Canada that required me to take multiple flights to get there from my hometown of Houston, Texas. I was flying to Victoria, Canada, which is north of Seattle. I had to take a couple of flights with a long layover in Seattle. I wound up getting to work exhausted and starting my week in deep exhaustion. One of the key parts of burnout is exhaustion. I was feeling tired and was totally unable to function. So, I would get there extremely tired.

It was a complicated project where I had teammates in Canada, and I had an offshore team in India so I was managing across multiple time zones. Because it was so stressful and I was so tired, I began to have a sense of reduced personal accomplishment, which is another burnout factor. This is where the things that you used to feel good about doing, you don't feel good about anymore. So you can't even celebrate your wins. I also felt depersonalization, which is the third aspect of burnout. That's when you have trouble even seeing people as people. Since you're so exhausted, you don't have the satisfaction in your work that you're used to. Instead of seeing someone who may just be behind on their work as a person struggling, you see them as an obstacle in your way. So, we often began to not treat people as well as we should.

I had all the three canonical aspects of burnout, I was exhausted, I didn't really get satisfaction in my work anymore, and it became harder to see people as people. I flew in Sunday night, exhausted, and struggled through that Monday. On Tuesday in my hotel room, I looked up at the ceiling in this hotel and I couldn't move. I was just so tired. I was sad. And I was like, "I just can't sustain this."

Eventually, I got some caffeine from somewhere and then made it through that day and then made it through the week and then until that project was over. That was the first time that I understood that what I was experiencing was burnout. Over the course of that project and in the years since, I began to understand what burnout is. More importantly, I learned the things I could do to build up what my wife and I refer to as burnout resistance. We can talk about that more later.

We definitely will. How many times have you been in what might be considered a burnout state in your career? Was it just once or was it more times?

It's definitely been more than once. Thankfully, over the years I've developed techniques to reduce the chance that I'll fall into burnout. But it's been a handful of times where I felt, "I don't know if I can do this anymore,". However, by building up my burnout resistance and by having a supportive wife and supportive friends, I began to find myself less in a state of burnout and able to navigate the built-in stress in software development and in this industry. And so I became less susceptible to burnout. But it took work. One reason that I'm talking with you is that I've learned things that have helped me avoid burnout. I've talked to lots of people as well, and I've gotten techniques that I've used to manage stress and avoid falling into burnout.

I love hearing your personal story when you were like, "And then I got caffeine and then I kept about my day," it's like that is such a, "Yep. That's what happens when you're in burnout sometimes." You're like, "Can I go forward?" Especially when we don't have those skillsets of knowing how to resist it. People think leaders don’t get burnout. I’m like, “Are you kidding me?”

Absolutely. When I was in Victoria, Canada on that project, I was the lead for that team. What people fail to understand about leadership – because they see our calendars and they think that all we do is just in all-day meetings, shooting the breeze, figuring out what we're going to tell people to do – is that these are complicated and often technical problems. There are also people problems, there are organizational problems, there are political problems, and they're gnarly. It’s very different from being an engineer where you just figure out the way forward and all your tests pass and you deploy to production, you're all good. There are often very few playbooks for the work that engineering leaders do. So that makes it even more stressful.

Another thing about being a leader that I'll add is that the things that we're doing now often don’t show their effects for months or years or never. So we don't have the feedback loop of failing tests or deployments being caught by CI/CD which provide breadcrumbs for figuring out what happened. Those long leadership feedback loops are also very stressful. So there are multiple parts of being a manager or an engineering leader that are extremely stressful that you often don't even understand until you get there.

Leaders are extremely susceptible to burnout. Burnout is an equal opportunity force. Individual contributors and leaders and managers and VPs, all the way up to the top of the company, are all susceptible to burnout.

I'm super passionate about helping everyone at all levels become more burnout resistant and to help people avoid falling into a state of burnout.

Yeah, it's true. It's good to dispel the myth. I also think there’s a massive weight of responsibility you feel to get decisions right. There’s so much uncertainty and ambiguity. And as you said, those feedback loops are really long. I think that that contributes to making them as much or even more at risk for burnout.

Absolutely. And leadership is lonely. Often you have your team that you're responsible for, but your team often doesn't want to hang out with the boss. And you usually don't get the same kind of honesty that you did as an individual contributor.

So the feeling of being a part of a group and being social with them is often lost when you become a leader. You are the Directly Responsible Individual (DRI) for your team. People are going to come to you and you alone to figure out how well your team is doing. If there are problems, they're going to come to you. That loneliness is also stressful and another key contributor to burnout.

I never got close to burnout until I was a COO. We were going through acquisition. It was lonely. I had a very clear realization, "Oh, the rest of my team does not consider me part of the team. I have all these things and I can't talk about them. I'm trying my best to be as transparent as I can." It can lead to feelings of, "Am I doing a good job? Does my work have meaning?" Which I think contributes to burnout, too.

Absolutely. You really hit the nail on the head where you have all those responsibilities. Your team may see you no longer as someone that they trust, if you were ever a member of the team, because some people go from being a team member to being a team leader, so you lose that. You are also privy to sensitive information that’s very private that you can't share. So you have the burden of all this knowledge that you can't share, but you know that the knowledge, when it comes out, will change people's lives. Often when it does out, people wonder, "When did you know, leader, about this? Why didn't you tell me?" You have to tell them, "I couldn't have told you because I had to respect the privacy of the people involved." These are all things that you really don't know until you're a leader or you have access to that kind of really private sensitive information that only leaders are trusted with. It's hard to know what that feels like until you’re there. It's heavy and it's hard, and it also causes people to be extremely stressed out.

I don't think I knew at the moment that I was in it. I think near the end of my role it was probably just feeling like walking through sludge. I don’t think I quite recognized it. What was it like for you to feel exhausted, be a role model and lead?

That makes it even tougher because I was exhausted. I realized that I'm not on top of my game. One of the things that burnout takes away is peak performance. Your body is struggling to process and to do the things that it does, to be able to be a problem solver or to be able to come up with novel solutions. It is extremely hard to do those things when you're not at your best. When you're in burnout, you're not at your best.

So, I wasn’t at my best, but I also realized that as the leader, people were looking to me to model how we should act. That added to the stress, which made it even harder. That was one of the many different forcing functions for me to research what I was going through and it has a name: burnout. I also found that there were ways to combat it. I realized that "I need to show up for this team that I'm responsible for, and I'm not showing up as my best self. I need to figure out what I can do to show up as my best self to lead and help them deliver software, and also to for them as human beings." And that was a big reason for me to address my burnout because I wasn't able to support the team that I really cared about.

When you were in it were you able to realize it? In mountain climbing, they call this a self-arrest. When you’re falling, you take your ax and grind into the mountain to stop yourself. Were you able to recognize and recover or self-arrest while you were in the role?

Well, one, Suzan, you are way more athletic than I am because I would never climb a mountain, I just would fall off a mountain. (chuckles) So let me just say that. I don't know anything about mountain climbing. But, my answer is, no, I was horrible at understanding when I was burned out. This is why I go into detail about the symptoms of burnout because most people don't realize when they’re burned out. My self-arrest didn't come from self awareness. I think it was like a “wife-arrest” because my wife realized it when I flew back home to Houston after being in Victoria, Canada, during the week. My wife was like, "What's up, dude, you're just not fully here and you spend half of the Saturday in bed and you have to leave Sunday night. We're not getting, we're not getting anything from you that we need from a husband and a dad."

My wife pointed out to me that not only was I not showing up for the people I was responsible for at work, but I wasn't showing up for the people that I loved at home. My wife loves me and cares for me, we’ve been married for 21 years now, but she's very honest with me, which I appreciate. A big thing about burnout is recognizing that often often won't be able to detect it in yourself. That’s why it's so important to have real relationships, whether it's a spouse or a partner or a friend group, or a community that knows you. A big part of understanding burnout is having people in your life that understand what's your normal profile. How are you normally in terms of how you interact, how you engage, and how you present? Often when you burn out, it's a slow degradation in who you are.

It's almost like when you start working out and you see yourself in the mirror every day. You probably say to yourself, "I'm not really changing. This isn't working." But then you run into someone who hasn't seen you in six months, and they're like, "Oh, wow, you're looking really fit." And, you say, "Oh?" because you see yourself every day. You don't notice the change. Well, burnout is very similar in that often you don't see the degradation in your performance and you need people that know what normal you is like to call out to you that you're not the normal you. That’s often the catalyst for engaging in your burnout state. Hopefully, people see it in you. Maybe they won’t use the term burnout, but that's often the way that you realize, "Something's going wrong and I need to work to make it better."

How did you get yourself out of it?

I wish I could say that my wife pulled me aside, and she shared with me the feedback, and I immediately realized, "Oh, I need to do something." If you ask her, she'll say, after several long weekends of her telling me I wasn’t being myself, it finally sunk in. Eventually, I got the message. I never want to be the person that says, "Here's how you wave a magic wand and it’s all fixed," because that's not how life works. It took some time. It took a few weekends, but I eventually got the message that "Okay, I'm not showing up the way that I want to. Something's going on." And I began to do a few things to change my environment because there are often some internal things that you can do to resist burnout, but I think a lot of it is in the external environment.

So I went to my manager and negotiated, "Hey, I need to spend some time not flying here and going through this multi-hour layover in Seattle and all this time changing flights. And, I need to spend a week once a month working from home. Since I have a good track record here, I’m confident this change won’t negatively impact the quality of my work. I’ll still be able to deliver at the same level that I'm doing now, if not better." That was one of the things that I did. I realized that I needed to give my body time to heal itself because I was doing all this traveling, staying in hotels, eating hotel food, and working long hours.

I had to make health changes to improve my body because a lot of burnout is your body just physically responding to stress. So I made a change in my external environment to better improve my internal mechanism. That was a big thing. By making that change, I saw an improvement in my mood, my mental clarity, and my ability to do my job at the high level that I always tried to do it.

The other thing that I did was take that time at home to really firm up the relationships in my family. So being in Victoria during the week kept me away from doing things with my kids and going to their tee-ball games or their activities. So really investing in the human relationships that were very dear to me was important because I found that human relationships lubricate stress. Meaning, you may be being ground up by life, but if you have great relationships, that helps keep you together. There's the old proverb, or I guess it's become a meme by now, "If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to go far, go together." So I got together with my loved ones and stopped being alone because I needed to go far. I needed to have a long-term view of my success, and that meant investing in the relationships that were really precious to me.

Also, I had to focus. I had to go to my manager again and say, "I have responsibilities on this project. There are some other projects within the organization that I'm working on. I'm going to narrow what I'm working on to bring my best self to this work." We often get so diluted by saying yes to everything, that we don't have any space to say yes to what we care about. I always tell people that “no” is the most powerful two-letter phrase in the English language because you have to learn how to say “no”. I began to say no to a lot of the things I was being asked to do in that company outside of that project. By doing that, I opened up opportunities for me to really focus on my work and do it better. It also took away a lot of the stress.

It's so easy to say yes. We live in a world where we want to be hyper-productive. But by saying yes to everything, you lose the ability to say yes to what you really care about. Saying no helps you say yes.

The important thing that you need to do is understand, "What are my values and what are the things that are important to me, and what are my limits? How far can I go before getting burned out?" By understanding your values and knowing your limits and protecting them, you'll be able to say to yourself, "When things come to me, these are the things I need to say no to." It should be the majority of things. By doing that, when the thing comes around that aligns with your values and is within your limits, you'll be able to say yes to work that's way more impactful and way more important, and you'll be able to do those things without getting burned out.

That’s great. There's such a masterclass there. How do you make yourself burnout resistant? Is it the same roadmap you shared or a different one?

It's the same roadmap – it's investing in my relationships, it's investing in my focus, and it's investing in my health. I learned all of those things on that project in Victoria, but ever since then, as I lived my life, I've gotten better at applying those three aspects of burnout resistance, which, again are relationships, focus, and health. Those are my keys to mitigating stress and avoiding burnout. That's been really, really amazing.

I want to explain why my wife and I say burnout resistance. I used to think I that I needed to make it impossible for me to be burned out so that burnout never happens. But thinking it's possible to end burnout is like thinking it’s possible to end crime. We're never going to end crime because crime is always going to be around. I think burnout to a certain degree will always be around us, but, hopefully, it’s at a distance rather than up close. We can do things, like we do with crime, to resist or to reduce the risk that burnout happens.

One thing that we want to do with burnout resistance is to reduce the risk that people fall into burnout. It's not like a binary, "I'm burned out or I'm not burned out." It's like an analog curve. So, it's really important that we understand where we are along that curve and to put into place techniques that help us resist going all the way over into burnout.

There's always going to be a load and things coming at you, but when you realize either big things are happening or you're having a big response to a lot of little things, you learn to stop them from happening. You want to be able to build up your ability to resist those big bursts to navigate getting through them.

There are two things I want to pull out. One is we can't stop them, but we have to recognize where we are on that curve. Two, those pillars are important – investing in your health, relationships, and focus. That is incredibly relevant for leaders. I see leaders let go of them all the time due to the sense of responsibility and wanting to give to the team. People say leaders are selfish. What I see is giving and not investing back in themselves, their health, or their relationships.

Absolutely. I’m a Staff Engineering Manager at GitHub. I'm not a VP and I'm not a CEO, but I still feel the responsibility of not wanting to let people down. And it's so easy to say, "Okay. There's this problem and this problem and this problem over there, and I'm going to be all over it. I'm going to run around all over the place trying to solve these problems or do these things for my direct reports or for my boss or whoever"

What often happens is that you let everyone down by trying to make sure that you don't let anyone down. You have to be able to narrow it down to a handful of critically important things where you can make a contribution that’s deep and meaningful.

It's tough because I know at GitHub we hire extremely capable people. Extremely capable people often overestimate their capability. They do way more than they can sustain and wind up being burned out and stressed out because of that. One of the things I tell people is, "You can't do everything that you're capable of doing. You have to do what's ultra-valuable to the people around you and to yourself." That requires saying “no” and that requires focus.

Part of your job as a leader is to recognize when your team is heading to this state. How do you notice when other people are heading in that direction so you can do what your wife did for you? What are the signs you notice?

This goes back to the adage that you need to dig your well before you're thirsty. By that, I mean that you need to know your team before you need to know your team. When I was going through a really bad bout of burnout, it was my wife who identified that I was diverging from the normal profile of the human being that she knew and loved.

You have to understand the people around you. This takes time, large investments of attention, being intentional, and noticing your team members. You have to know the normal profile of your team. That can be things like shipping speed, levels of communication in Slack or Teams, or whatever communication tool that you're using, or just the overall vibe of the team. You need to be able to do that at the team level, but also at the individual level.

Noticing these things gives you a sense of where the team is. That gives you the ability to dig in, investigate, see what’s really going on when the team seems off. It could be obvious things like "Oh, massive layoffs are happening in our industry. People are concerned about their job. That kind of tracks with what I’m seeing." Or, it could be more subtle things where people may be having things going on in their personal lives that are impacting their work life. That's why 1:1s are so critically important. 1:1s are probably the number one tool in my manager's toolkit. By having regular 1:1s you see the normal profile of a person and get clues for noticing when they diverge from normal profile. Then you can begin to investigate.

However, You never want to diagnose people as being burned out because you're not a mental health professional. So I would never say, "You seem burned out," or, "You are in burnout." Never say that. You can share your observations and say, "You know what? Hey, person Y, I noticed that normally this is how you typically perform when it comes to your work or how you interact with the team. Things seem to have changed. You used to never be late to any of our meetings, and now you're always five minutes late." Little small observations can help you lead a conversation to begin to help that person tell you where they are.

Those observations and having real conversations with people are how you help the team understand where they are and help them get connected to either tools or techniques or mindsets that help them to get to a better place.

I love your focus on the relationship. When you have that relationship they might feel safe enough to talk about what’s going on. Sometimes people feel overwhelmed and not getting the support they need, but they don't feel like they can say that because they're worried about what it means for their job. I love your focus on creating a human connection.

One of the cheat codes for being a manager and gaining trust is being vulnerable. Vulnerability unlocks vulnerability. So if you can honestly tell your direct reports, "I'm having a hard time in my personal life, I won't tell you the details, but that's impacting how I'm showing up to work," or, "I'm exhausted.”

When I'm vulnerable, people are vulnerable with me. That builds trust. That's what you can use, that's digging your well before you're thirsty so that when times get really hard, you're able to have that relationship to navigate that hard time together. It requires vulnerability. It requires putting down the facade that, "As the manager, I need to have all the answers and be perfect and all that." No, you’re a human figuring out hard things, too.

People like being managed by humans. It's okay for you to be human at work. And if you're a human at work, you are modeling that everyone else can be human, too.

If this piece resonated with you, please let me know and give the heart button below a tap.