Leading While Managing a Chronic Health Condition

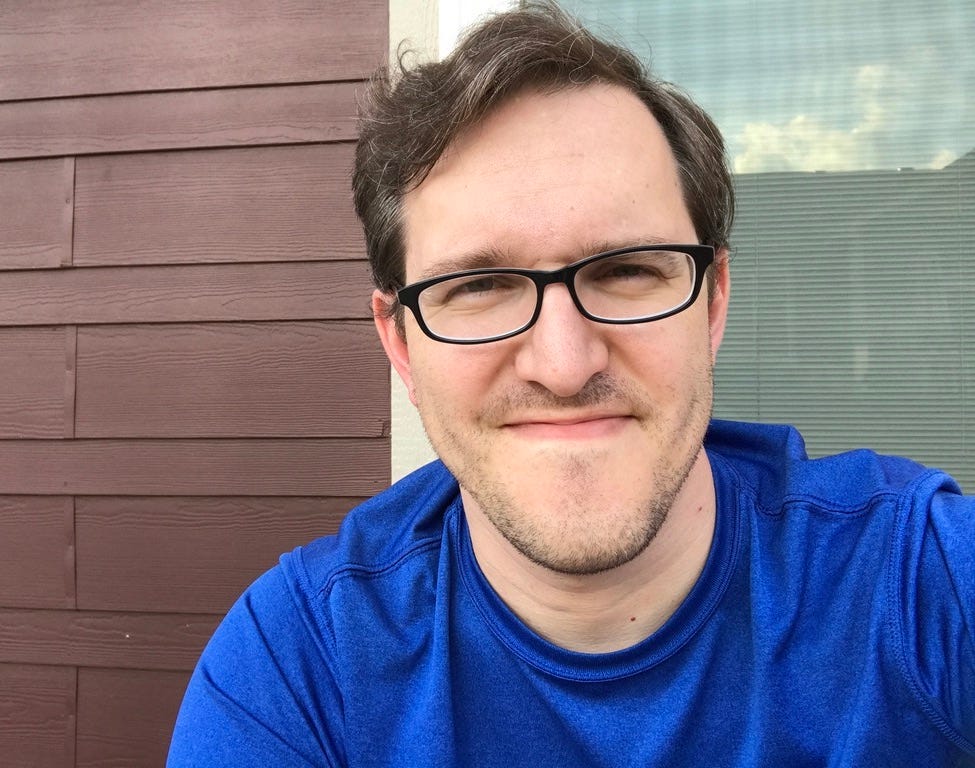

A conversation with Dizzy Smith, VP of Engineering, Edge & Node

Since the inception of this series, I’ve wanted to have Dizzy Smith, VP of Engineering at Edge & Node. I was happy he agreed to share his story about being a leader while navigating follicular lymphoma (a still incurable cancer). We also talked about why he went into management (despite swearing he never wanted to do it), his transition into leadership, and what keeps him up at night.

Your given name is David. How did you become Dizzy?

(laughs) A long time ago, while in college in the late '90s, I got involved with this project called Jabber which was pretty exciting. Like a lot of Open Source projects at the time, we hung out in an IRC room to work on the protocol. I tried to join IRC with handles like DSmith or DSmith55 or DaveSmith, but they were all taken. So, I wound up joining as DizzyD. I don't quite know where I got that from at the time, but I thought it sounded cool.

We worked remotely for a year on this thing before we finally met up in Denver, and when we met in person, people were like, "You're not David, you're Dizzy." It occurred to me that this disambiguation could solve a lot of problems! There were always four or five Davids in the office – at CenturyLink there were 70 or 80 of us! Anyway, Dizzy just became my handle and I've used it ever since, because it's easier for people to remember, there are a lot of Dave Smiths in the world and I just feel a little more special.

What a great story. I can imagine DaveSmith186348690. I have two friends who have the same first and last name... Kim Curtis. Which is not quite Dave Smith, but I have two friends with the same name.

Totally. It happens.

I had to ask because when I wrote to you about doing this, I thought, "Is Dizzy his first name? If not, what is his given name?”

Yeah. My first name's David. It drives my parents a little crazy because my mom is like, "I named you David for a reason." I don't know, you have to become your own person, I guess. But they're the only people that call me David anymore. Even my wife calls me Dizzy at this point.

It's a great name. It suits you. All right. And now will you introduce yourself—not just your name origin? (laughs)

My name is Dizzy Smith. I’ve been around technology for almost 26 years now, which is hard to believe! I was VP of Engineering at DigitalOcean for a bit, then a company called Packet (acquired by Equinix) and more recently Edge & Node. But I've worked on all sorts of different things over the years. The first 15 years of my career were mostly writing code. I worked on Jabber, I helped write PingFederate for Ping Identity, built distributed databases in Erlang, etc. I did a lot of other random stuff as well, and then eventually went into the management track.

I understand that when you were an engineer, you had no plans of becoming an engineering manager. So what changed?

Yeah. I had been an engineer for about 15 years before I decided to go into management and I joined a company called Basho to work on a distributed database called Riak. When I joined the company, I was certain that I never wanted to manage people, because people are non-deterministic, they're hard to predict. There are just a lot of feelings when you deal with people! I wanted to write code; that was my happy place. About three or four months after I joined the company, I noticed that I had two lumps on the back of my neck. I went to the doctor and they started feeling around and then they just went white as a sheet and it turns out I had stage four follicular lymphoma. It was pretty shocking, especially when you're in your early 30s because you still have that taste of immortality on your lips.

At that age, I still had that "I'm going to live forever," kind of feeling. Ultimately, though, what the doctor said was, "Look, we discovered this so late that we can sort of keep it in check for probably about 20 years with current medicine, but it's going to keep coming back and we're going to eventually run out of options for dealing with it, and then…that's the end." So I did chemo and that got me into remission pretty quick because the drugs are effective on the first pass. They're just not a cure. In that whole process of doing chemo, you really confront your mortality. There are days when, frankly, you wonder if you’re going to make it.

When I got to the other side of chemo and into remission, I thought, "What is it I'm going to do with these 20 years?

On reflection, I realized that I loved writing code and was moderately good at it, but that wasn't really the most fulfilling part of the work I did. The most satisfying parts of my career up to that point had been coaching and mentoring and leading teams, although I'd never managed people. So, I thought that I’d give management a try, with the belief that I could do better than some of the bosses I’d had up to that point. I had been in a number of rough environments; I wanted to give it a try and invest in people.

When you're faced with the prospect of death, the question becomes, “If there's a memorial service for me, what is it I want people saying? How will I be satisfied that I have lived my life fully if people show up and say this thing?” I realized that for me, that thing was, “Did he invest in me? Did he help me do something amazing?” In addition, I know there's a limit to the things that I can do on my own. There is no limit, however, to my ability to encourage and inspire and do what I can to uplift other people who are way smarter than me and far more capable. That's something I can do and make the world a little bit better.

That's how I got into management. When I came out of chemo, they were looking for an engineering manager. They had five engineers. I was one of them. I was like, "You know what? I want to give that a try."

When I was in my 20s, I almost died from a bacterial infection around my heart. It was squeezing my heart shut. I basically flatlined. I knew I was dying. And, that if they don't get here in five minutes, I was gone. They got there, luckily, obviously and I had emergency cardiac surgery.

Afterward, someone asked if it was the worst day of my life. It was, but it was also the best. Because after that, I started thinking about what would happen at my funeral and what legacy did I want to leave? I don't think about death every day, but I think about it a lot. And I'm curious, you're a number of years away from the diagnosis now. Is that still present for you?

Oh yeah, yeah. There are a lot of illnesses and cancers that once you get five years out, you're considered cured because the odds for relapse are very low. That is not the case for my particular kind of lymphoma, which is still considered incurable. Although I just had an experimental treatment last summer that maybe, fingers crossed, could be a cure – but we just don’t know yet.

(we both cross our fingers)

I spent a lot of time talking to my therapist about this. They give you an oncology-specific therapist at the hospital these days. One of the things that I've talked to him about is, that I'll be fine for a couple of months or even a couple of years, and then it comes crashing back down. It's a thing you always think about because you know that it's going to come back. It's just the way it works and it's really hard.

It doesn't go away. Since it's incurable, essentially, it's ever-present. Someone once asked me, "Isn’t it depressing to think about death every day?" I replied, "Not really. I think it helps me prioritize and think about what’s important.” Now, I don't have an incurable illness. I mean, I have a chronic illness, but it's not the same.

I mean, I would categorize what I'm going through right now as pretty much a chronic thing. There's definitely a time limit; we don't know what it is, but it's far enough out right now that it's chronic. Does it get tiring to think of death? Yes, it does. But to your point, it can be a catalyst, a source of energy as well. It kind of depends on the day, honestly.

I think the parallels of leadership are very similar. There are days as a leader where you are run down and you encounter problem after problem and the weight of it simply crushes you. Then there are other days where you run into problems and you're just batting them off and you're doing your thing. And it's great. I think they're very similar sorts of sets of feelings.

That was not where we intended to go. “Talk about death” wasn’t on my questions. (laughs) But I appreciate you talking about it because I think you have a unique perspective. So, after learning your diagnosis, and going through chemotherapy, you’re able to reflect on what’s important and decide to go into engineering management. So you were pretty new to a diagnosis and you're in a new job. How was that?

Yeah. So, I took on the engineering manager role. Now, to keep it in perspective, when I took on that role, that was the entire engineering team for the company. There weren't a lot of people in the company, I think, 12 or something altogether across all the functions. I took on that role and the first thing they told me was, “We need you to double the size of this team in the next six months.” And I'd never hired anyone before. So I had to sort of discover a lot of this stuff myself. Figure out how to interview people, which is a whole other fun topic, and so forth.

Over the course of about 18 months when I came back from chemo, I eventually wound up becoming the VP of Engineering. I was responsible for not just engineering, which became about 30 people, but also professional services and support. There were about 90 people altogether in that group by the time I left Basho. Now, Basho's complicated for me personally – it’s a source of both pride and shame. I had never created a team or created a culture or anything like that before. I just tried stuff, I tried to treat everything as an experiment and do something, learned from it, and do something else kind of thing. We hired some amazing people, but I also inadvertently created a homogenous, white guy culture.

I told myself that I was trying to create a diverse environment, but I wasn't really. Now as it turns out my wife, Sarah Drasner, also worked there – one of my last days at the company was one of her first days there. So we sort of passed like ships in the night. She was a front-end engineering manager working on other parts of the product. She wound up having the interface with some of the people that I hired and it was terrible. The engineering culture was hostile to women.

When we started dating, five or six years later, we had some hard discussions about that when we started dating, because in my mind at that point Basho had been my shining achievement. I had started from a tiny team, hired a bunch of people and built teams and features. From her perspective, it was a sort of trash fire to work there because some of the people – not all the people – but some of the people were just awful. All the things we clearly identify as hostile and homogenous culture she had to deal with.

That set of conversations forced me to rethink what it was I did as a leader at that place. Now I look back on it and I'm proud of some of the work I did, but also recognize how naive and ignorant I was about some really important topics. I also understand in a significant way just how critical it is to get some of this cultural and diversity stuff right; you can really injure people as a leader if you're not paying attention. For me, Basho was a great experience. I learned a lot. I also messed up a lot and it set the tone for things that I would learn as I continued my leadership journey.

I love that you talk about that because I think these things do happen and they're inadvertent. I mean, we're well-meaning but we don't know. Did you have any training when you went into management and then VP of engineering?

I had no training. I didn't really have any mentors. I didn't have any of that stuff. As I've worked at other places, I've really tried to pay attention to making sure that we're coaching managers and giving them good guidance and support. But no, I didn't have any of that.

I think that it is really important to note that, yes, it was inadvertent, but that doesn’t absolve me of responsibility. It took me a while to come to grips with my failures here. It was my responsibility to create a safe and diverse environment and I didn’t do that.

I think as leaders we have to be willing to look back at our actions and be willing to be critical of ourselves because we're not writing code or if the code messes up, it's like, "We displayed the wrong thing or we wrote the wrong thing in the database," whatever. In leadership, we're materially affecting people's lives if we mess up and that should weigh heavily on us and we should treat that very soberly in our actions and our learnings.

There's not enough training and support for managers and leaders, and we have a responsibility to make sure that we're doing our best. Both are true. It's part of why I do my work. I want to give people more support so that we can have better environments. My mission is to create environments where people can thrive. I think you have a similar kind of mission?

Yeah. Mine is to create environments where people can do the best work of their lives. That was a thing that evolved for me sort of over a series of leadership roles. I knew I wanted to do that at Basho - I did my best - but I really messed some stuff up in the process! I kept refining it as I went on in my career and trying to make it better and better. I think a big role of leadership and managers is about creating environments. We're not there to tell people exactly how to go do a thing or micromanage them. We're there to create the environment, so they have the clarity of vision and everything they need to do great things. It's about amplifying.

I hadn’t realized that part about you and Sarah. When you left Basho, you were proud. At what point did you begin to grapple with that maybe the results were mixed in your view?

I mean, it was five or six years. One of the things in my experience, now doing this almost 12 years, is that when you become a manager when you move into the manager track from the individual contributor track, one of the first things you run into is that your feedback loop becomes much longer, very quickly. If you're an engineer writing code or whatever, your feedback loop is typically a couple of hours to a couple of days. You'll know if you messed up if you made a bad decision, there are things that are longer range, but a lot of times, you know pretty quickly. When you move from an individual contributor to a manager role, your feedback loop goes from a couple of hours to a couple of weeks, maybe a month.

When that happens, you feel like the world has dropped out from under you. It's like you're in space all of a sudden, you have no feedback for when you move or what's going on, and it makes it much harder to learn. So when you become a director, a manager of managers, feedback goes three to six months, a VP can be years before you're going to know definitively! So it's not surprising to me, in hindsight, that it took me so long to realize how much I had messed up. It's just a part of that learning curve for management.

It's such a good point too that those feedback loops become long. Sometimes you have to work at creating those loops.

Yeah. I think this is why people who are managers often say, "I just don't know what I got done today" because what they got done today was they made a decision in the meeting. They clarified communication between a group. They did things that you can't see the immediate impact of. It's a part of what makes management or leadership of any kind really difficult because you just don't have that. I agree that you can create those feedback loops and we try to, but there's also the aspect that when you’re coaching a person, seeing that change can take a long time sometimes because they have to integrate it, they have to agree with it. There is a lot of acceptance that has to happen there - most of which you don’t control.

Agreed. I left my last leadership role three years ago and I still think, "Oh! Did I get that wrong? What could I have done differently at that moment?" Not like I'm not ruminating on it every day, but there are moments that I wonder.

Yeah. It's the thing that wakes you up in the middle of the night. You wake up just out of a dead sleep and you're like, "Well, maybe I shouldn't have said that to that person. Maybe I shouldn't have made that decision." There's always these things that pop up and we're like, "Oh yeah, maybe that was a mistake." And it can literally be years later.

So you recognized it a few years later. What role were you in?

That was just before I went to DigitalOcean. So, I was at CenturyLink. I was at a company called Orchestrate, which was a little startup, like ten people or something like that, but got acquired by CenturyLink. I was there for like six months or something, but Orchestrate was where I was at when Sarah and I started dating and we were working through a lot of these topics.

When you went into DigitalOcean in a leadership role, was it something you consciously thought, “I’m going to change these things?

Yeah, it was when I went into DigitalOcean (DO). At the time and this was what, six years ago now, something like that. Keeping track of time gets weird as we get older. But when I went into DO, it had a reputation for being “Digital Bro-cean”, which was not great. The team that I took on had 20 people on it, and there was only one woman. There just wasn't a lot of diversity on that team. I went in there knowing that I want to do better at this, I want to create a diverse and vibrant culture where people do the best work of their lives. That was my mission when I went into DO, and we did it. By the time I left our engineering management team was fully gender-balanced. There were only two white guys on that management team of ten or so. At an individual contributor level, we were up to 40% underrepresented people, with a substantial portion (30%) being women. But it took three and a half years to get to that point! It was a really heavy lift over time in addition to all your normal startup stuff. But I went in intentionally trying to do that because I wanted to atone (if that’s the right word) – I wanted to do the right thing by people. Basho still weighs heavily on me for the sort of environment that I inadvertently created. I wanted to do better.

I really feel that. And I love what you did at DigitalOcean, the way you thought about it and being very conscious about it. After that, you went to Packet?

I left DigitalOcean, I guess, at the beginning of 2019. I took a six-month sabbatical because DigitalOcean was rough. It was not an easy environment. There was a lot of turmoil over the years, but they've gotten to a much better place now, which as a stockholder, I'm super happy about. But at that time, it was a startup that was growing up and so I wound up taking six months afterwards because the thing I realized is that it's really important as a leader to have some time between things. Otherwise what happens is you wind up taking all your fear and trauma from the previous environment with you into the next thing. Then you can wind up overlaying models from the previous environments on the people in the new environment – and they don’t always match up.

So, I deliberately took some time off to try and recover and rest a little bit. It was great, I took the kids to the pool almost every day. I played Xbox. It was a great time to recover from the burdens of leadership. I think people don't quite understand the emotional toll that leadership takes. If you're doing it well, if you're caring about people, it is not a minor thing, you're giving of yourself, your emotional energy. At the end of the day, a big part of the reason why I'm not a believer in having managers and directors write code is because there’s just no emotional energy left to write code. That part of my brain just doesn’t work after I’ve finished a day of management.

That six months were very healing for me. And then I popped my head up and started looking around and I had looked at Packet's website before, because I wanted to go build another cloud, working on a cloud at DigitalOcean was a ton of fun, really hard, and interesting problems. I wanted to do it again and see if I could do it any better.

Packet was building a bare-metal cloud, but they had no roles available and I really wanted to be VP of Engineering. So I was talking to recruiters and stuff, and then the day after I popped my head up, a recruiter reached out to me and he's like, "Hey, I'm looking for a VP of Engineering at Packet." my response was pretty much, "Yes, sign me up." So I went through the interview process and I remember going to New York for the final set of interviews with Zach — who you also interviewed and Jacob — and we were walking to the train together and at the end of the day and I turned to him and I was just like, "Look, I really hope you'll hire me. I know this is a bad negotiating tactic. But after talking with the people here, I want to be a part of this, and I think that we could do amazing things together." He looked a little surprised because I think normally, you're not supposed to say that, you're supposed to be a little cool and such, but I'm not really a cool person. That explains it.

So I went to Packet. Packet was kind of similar to DO. They had a working product and they wanted to expand it and the team size was similar to when I went into DO, the engineering team was about 20 people. I was there for, I guess, three or four months when Zach pulled the VPs aside and told us that Equinix was acquiring us. We went through the whole due diligence thing, and eventually landed inside Equinix, in March of 2020. The deal closed the day before everything really started to shut down from the pandemic. So, I was very happy with the timing of that.

That was an interesting time. I don't know if I have my timeline right. Didn’t you have a resurgence of cancer around the same time?

Yeah. The deal closed, the pandemic hit, and then two weeks later, I found out that I had relapsed for the third time. Getting acquired is a whole thing – it is a very high-stress time because you're getting pulled into an organization that already exists. Equinix in particular was very complex.

It was very stressful, and then to have the relapse at that point just compounded everything. The thing is, all of the treatments I do for my kind of cancer affect my immune system – since the cancer is in the immune system. When the pandemic hit, the doctor said, "We don't want to treat you right now, even though you're relapsing because we don't know when there's going to be a vaccine for COVID. We don't even know how to treat it, and we don't want to knock down your immune system and increase your risk," because ... Anyway, you can guess sort of all the reasons there. But it was super duper stressful.

Yeah, that's intense. It's a lot coming at you at once — a pandemic, your health, and an acquisition. Acquisitions are very demanding even when they go well, the transition is just so much.

Yeah. I mean, there's just a lot of changing of gears, learning the new culture. There's just so much that goes into it that's really tough and unpredictable.

Leadership on its own can be demanding. You have to care, but it’s hard. The worst thing somebody ever told me was, "You don't care." I cared so deeply, and to care right, we have to put a lot of energy out. It's a lot of energy towards other people, and also thinking about, "Did I make the right decision?" And introspection, which is not always easy. You were also amid a resurgence of your cancer. How did you manage it all?

Well, when I had the appointments and tests, I wound up taking a week off or something. I didn't deal with it well. There was too much going on; there were too many changes at the same time! This was also the time when schools shut down. Then we were – Sarah and I – we'd get off of work at night and do another five hours of homework with the kids. It was a crazy time. So I can't say that I had a great process for all of this. I was very not zen about it. I was just trying to keep my head up above water.

I wish I could say that after dealing with this for 10 years, I figured it out, but I think it's like the monster in the closet that periodically comes out, and you're just like, "Leave me alone!" I didn’t want to deal with cancer right then, because I was trying to be there for people. Especially at this time, everybody in the world was going through these really hard transitions. There were a lot of people who were suddenly working remotely, but they were not used to it. A lot of companies, Equinix being one of them, just Zoomed everybody to death. And it wasn't just Equinix that did that, from what I heard, most companies had that problem. Nobody knew how to transition from a very synchronous culture in-person to a very async, remote culture. So what most organizations did was port the synchronicity into Zoom.

Everybody was going through a lot of stuff and it was tough to be there for people and support them and hold the organization together and also deal with all the normal acquisition stuff. It was just a lot. I don't think there's a secret to it beyond paying attention to how you're feeling. I think this is probably one of the most important leadership lessons: the first person you have to manage is yourself.

When the relapse happened, and the doctors told me they were going to just do watch-and-wait, it was hard to manage myself. We wound up doing radiation later in 2020, but that didn't really have the effect that they wanted because I'd done radiation a couple of years before, while at DO. Eventually in 2021, I was able to do an experimental treatment that was pretty significant. When I did do that, I actually took medical leave, which turned out to be one of the best things I could possibly do.

I think that reinforced for me the importance of planning for succession, planning for the org to run without me. Happily, my team at Equinix was set up in a way that allowed me to take a leave. That was the first time I'd ever had a full medical leave for cancer treatment. Being able to do that, because I had a great management staff in place was fantastic – and they did amazing stuff! I mean, I would argue they did better with me gone. So, that was great because I was able to really rest and recover.

How long of a medical leave did you take?

About four months? Just the mental aspect of gearing up for treatment, it was an experimental treatment, so we had to drive 20 miles to the hospital every day for two months because you had to get your blood tested every day. They eventually admitted me for a couple of days and so forth and so on. So, it was a whole thing.

It’s really interesting too that you'd been in a leadership role, you'd been dealing with your illness for many years and it was the first time you took a medical leave.

Yeah. That was dumb. You should take medical leave when you have a serious illness. I have been very adamant with my managers and directors thereafter. I was having a conversation the other day with someone I'm coaching and they were talking about, "I know I need to take a sabbatical, but I'm going to defer because I want to wait for this other person to get back from their thing." And I'm like, "No, you've been doing this for a long time. It doesn't sound like your company's in a situation where they're going to keel over if you take some time off, but you’ve got to do it because if you don't, you can't be there for the people you're leading and you're managing."

It's a heavy responsibility that you bear when you're responsible for people and taking care of them. If you can't be there for them, you've got to do what you need to do to take care of yourself so you can be there for them.

I call that airline state of mind — put your mask on before helping others. I think leaders often feel so much responsibility that they forget. Medical issues make that more intense.

You and I follow each other on Twitter. One of my favorite things about you is how transparent and vulnerable you are. I remember you tweeting last year about shedding tears that day because you were relating about how tough management can be. What makes you so open? Have you always been like this or was it a conscious decision?

I think that's just kind of the person I am about some of this stuff. I do think that there's an aspect of a vulnerability that serves us well as leaders. It’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking that leaders should have it all together all the time. But the truth of the matter is that leaders are people and sometimes we don’t have it altogether, just like any other person on the planet.

Choosing to be vulnerable makes you more approachable as a person. It's hard sometimes, it's scary, but it makes you more approachable as a person so that you're not just sort of this floating head leader person or whatever. You're approachable, people can talk to you and that's good for the organization because that means you're going to hear about problems.

You can go fix them, which is a big part of your role as a leader. I think being vulnerable also creates room for other people to also be vulnerable. If, as a leader, as a manager, you can admit that it was a hard day or that you made the wrong decision, that creates room for other people in your organization and other organizations you work with to also do that. The funny thing about admitting you're wrong or admitting you're overwhelmed is that it creates opportunities for learning and excellence.

If you're not vulnerable, if you're not open about this stuff, there's no reason to learn. There's no motivation there because you've never done anything wrong. It's something I do try to cultivate and I've found over the years that it's better to just be upfront when it's hard. There's a balancing act there, you don't want to constantly be like, "I'm broken all the time.” Leaders do need a certain level of confidence and willingness to to get up in the morning and face the scary things. But I think there's also room for softness and vulnerability. The best leaders that I've worked with are willing to be humbled.

I love that. Is there anything we haven't covered that you wanted to just share before we end?

I would just remind people that there’s no handbook for leadership. Although my wife is writing a management book (Engineering Management for the Rest of Us!) and I think she's captured some really seminal and amazing stuff. She's running core web infrastructure at Google, so you know she's a badass engineering leader. But that aside, there just aren't books out there that are going to teach you necessarily how to interact with all the different kinds of people or how to do all those things leadership requires. I would encourage people who are leaders to be sober about the responsibility they carry. It's not just about telling people what to do. You are responsible for the well-being of those people, and you should treat it as the critical task that it is. I wish someone had told me that. You learn it the hard way though, I guess.

If this piece resonated with you, please let me know and give the heart button below a tap.