Traversing the Neutral Zone

A common feature of leadership

Last week I wrote about the changes coming up in my business. There’s also plenty of it in my personal world as I help my parents navigate their later years. They’ve been living on a lake for the last 30 years. They’ve created a wonderful sanctuary where sparrows, chickadees and woodpeckers flit by their windows all day. Papa cardinal sits on a branch swaying in the breeze. He keeps watch over mama cardinal as she fills her belly with seed. Sandhill cranes stroll through their yard. Traffic is a family of canadian geese crossing the road for an afternoon swim.

My parent’s home no longer suits where they are in life so they’re in the process of selling their home and moving to an apartment. The past few months have been consumed with letting go of belongings and packing what they want to take. They’re picking out new beds and finding new furniture that fits into their new smaller space.

They’re grappling with what all this change means. They won’t get to see the baby sandhill cranes later this spring. They won’t be cooking anymore which is a relief but also feels odd. What if they don’t like what’s being served? New assistive walking devices will be packed alongside their favorite treasures. The reality of time beckons. They will no longer be home owners but instead, apartment dwellers for the first time in decades. As you can imagine feelings of confusion, loss and uncertainty have arisen. As I help them process leaving their home and veritable bird sanctuary, I’ve been thinking a lot about how we go through change.

This topic comes up frequently in my work as an offsite facilitator, workshop leader and consultant. Much of my work revolves around helping leaders navigate change. I’ve recently spoken on this topic. First at RubyConf about why leaders feel lost and how we can help them navigate the new terrain they find themselves on. The second, at LeadDev New York about the shift from manager to manager of managers. During these talks I spoke about the challenges of making the leap and the changes new leaders must make.

Today, I want to focus on a critical part of the process — the neutral zone.

*****

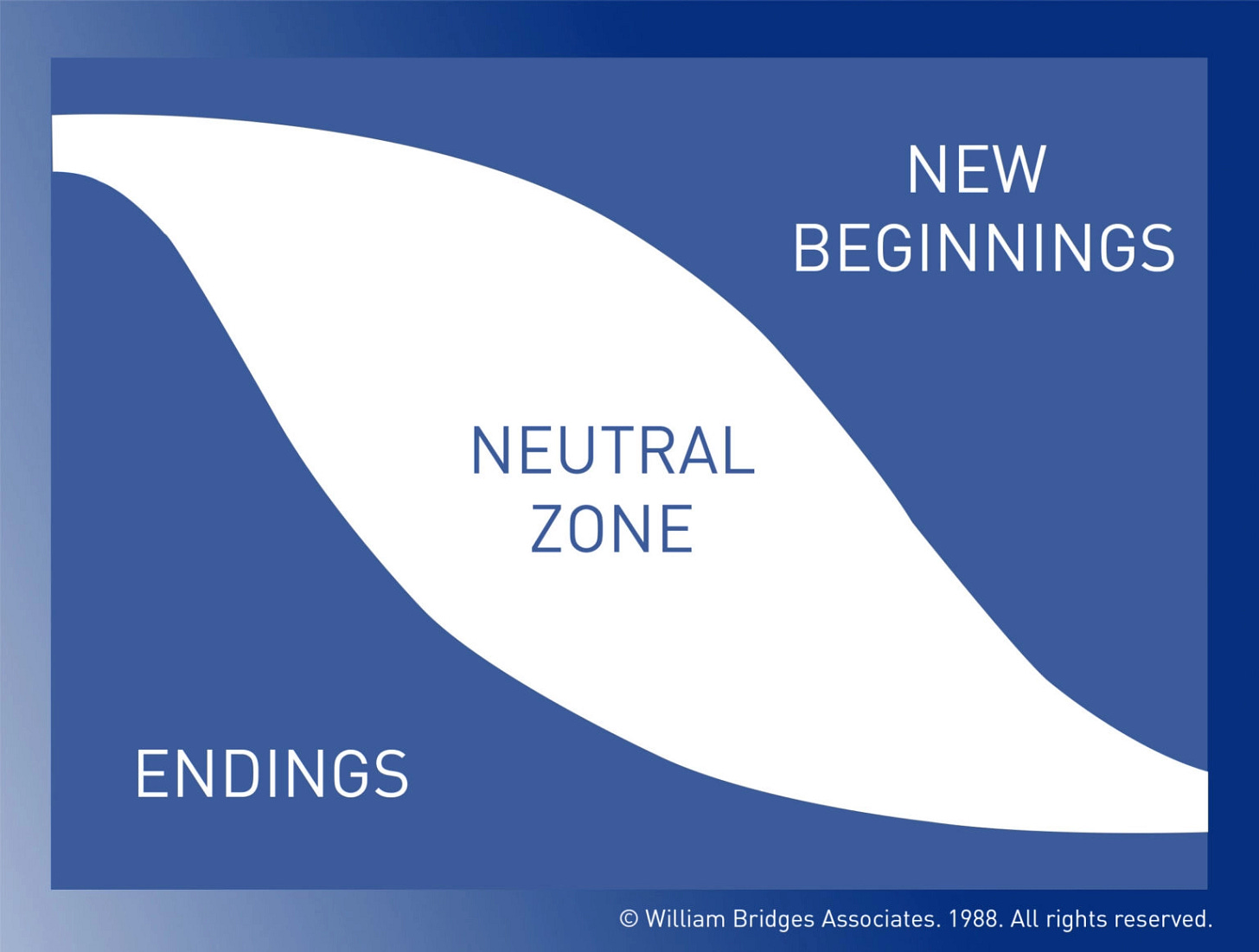

I learned about William Bridges book Transitions while in a grad school class on organization development. While it was written in the 80s, Transitions is a seminal work that’s still relevant today. I’ve purchased and given away countless copies. It’s the one I recommend the most. In the book Bridges makes an important distinction between change and transition.

Change is situational. Transition, on the other hand, is psychological. It is not those events, but rather the inner reorientation and self-redefinition that you have to go through in order to incorporate any of those changes into your life. Without a transition, a change is just a rearrangement of the furniture. Unless transition happens, the change won’t work, because it doesn’t “take.”

William Bridges

In the leadership world, change is the new job title, the new team, a new salary. While it’s easy to focus on the changes to be made, that’s actually not the tricky part. To be successful in our new role, we need to shift the way we think. We need to see ourselves, our work and our identity in new ways. This is what Bridges refers to as transition. It’s far more difficult.

When a change doesn’t take, the logistical pieces are rarely the reason. These shifts don’t “take” because we haven’t made an internal shift. We haven’t updated our understanding of ourselves. We haven’t figured out how we need to think and act differently in this new world. We haven’t moved through the sometimes complicated feelings that accompany change.

As Bridges says, “It isn’t the changes that do you in, it’s the transitions.

We often think of change as endings and new beginnings. There are actually three phases of transition — the ending, the neutral zone and then the new beginning.

Let’s say we have a new leadership role, with more responsibility or at a new company. The ending comes as we say goodbye to colleagues, familiar routines, the team we’ve been on for years. We think this letting go moves us into our new beginning. Instead, we land in the neutral zone. This is where we begin to make sense of our past experiences and what the new beginning means for us. While we’re no longer in the old situation, we’re not quite in the new one either.

This is because we haven’t done the inner work necessary to operate in the new sitaution. For example as a manager our value was in helping to ship the work. As a manager of managers our value is coaching the managers who help the people who ship the work. As our day-to-day slips further away from doing the work, we wonder whether we’re adding value.

We haven’t made the mental shift from managing the work → coaching managers.

We haven’t yet recognized that coaching is valuable. If we don’t see coaching managers as valuable, we won’t make it a priority. This means we’re more likely to continue to go back to managing the work, in the process micromanaging and disempowering the managers running those teams.

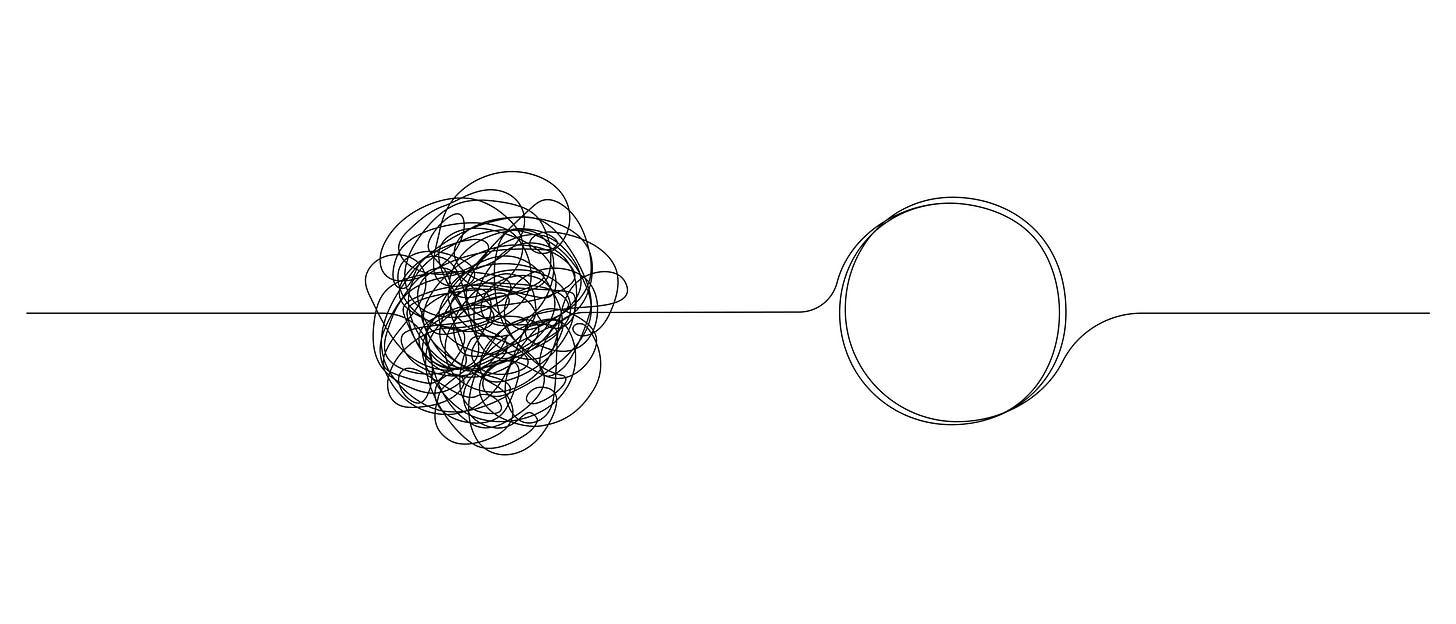

Despite the change, we’re still stuck in the neutral zone.

Neutral zones can be incredibly confusing, even chaotic. We might feel thrilled to have a bigger impact. We’re happy to have a say on strategy and other organizational matters. At the same time, it’s all new to us. We don’t quite know how to navigate the new context. We don’t yet understand the expectations. We don’t quite know how to behave. We’re still learning key skills like knowing how to influence others without positional authority. We’re learning how to delegate key work while still holding responsibility for it, which can disorient and unground us.

These new situations bring up bewildering emotions. As we make mistakes, we worry perhaps we weren’t ready for more responsibility. When we find decision making difficult, we may wonder why we decided to change roles. When we wield our new power in clumsy ways we might feel guilt or shame. We may even wonder if we’re qualified to lead.

We’ve made the change, we haven’t completed the transition.

When new leaders come to my workshops they’re often navigating the neutral zone — even if they’ve been in the role for a while. This phase lasts longer than we think — typically months, sometimes longer than a year. This is because transition takes longer than change. To enter the new beginning we must reorient ourselves. It’s the way to make the change stick. If we don’t, we risk staying stuck in the neutral zone. This is where I see too many new leaders fail.

You won’t traverse the neutral zone just once in your career but many times as you change roles, as you take on more responsibility, as you change companies. The next time you find yourself at an ending on the precipice of a new beginning, remember that you will enter the neutral zone — a time where you will experience confusion and even a loss of identity. Rather than pushing to prove your value, lower your expectations of yourself. Take time to identify what’s different now. Get clarity on the internal shifts needed. Create space to navigate the confusing and sometimes contradictory emotions that accompany transition.

Get yourself a copy of Transitions, use it as your guide through the neutral zone.

If this piece resonated with you, please let me know and give the heart button below a tap.